Hatches: The hatches that sat on top of the forward and aft conning towers served as the only access points into and out of the submarine. Scientists found one hatch was locked and the other was not. The forward conning tower was found unlatched. This could be significant, but the hatch was heavy enough that it would stay sealed while the submarine was underwater and upright. The aft hatch was found locked. If the crew had been desperately trying to escape, it is reasonable to assume both hatches would have been unlatched.

Ballast Pump Settings: When the Hunley mysteriously vanished, most students of history assumed the eight-man crew drowned. That may not be true.

The pumps are still in the same position they were on the night the submarine was lost. Those settings could reveal what steps – if any – the crew may have taken to try and save their lives.

A preliminary study of pump system shows that it was not set to pump water out of the crew compartment. This discovery suggests the crew may not have drowned, but died of some other cause.

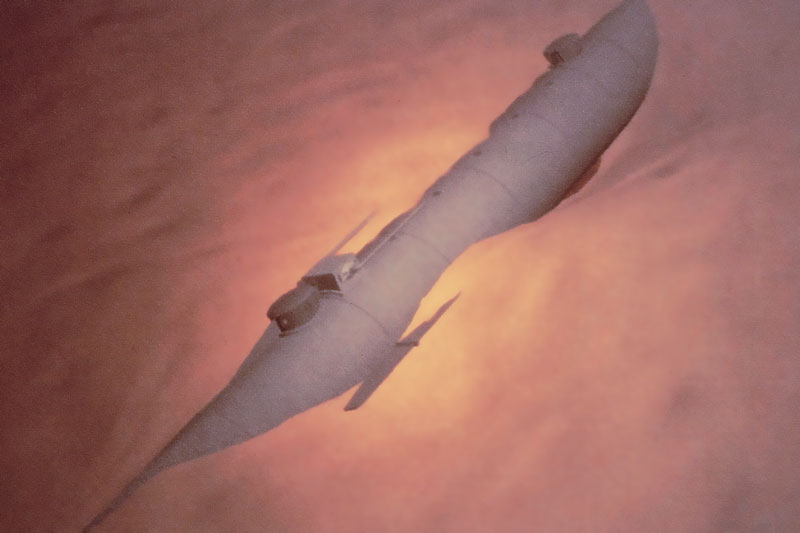

Blackout Mode: The Hunley was in Blackout Mode when she was lost. The submarine had a series of 10 topside ports that provided the crew a small measure of ambient light when the Hunley cruised on the surface. These small glass ports were equipped with iron covers that could make the ports watertight and also block any light from escaping the sub, and possibly alerting ships to their presence. These ports were all found closed.

Historical Records: Some historical evidence suggests the Hunley did not sink immediately after the attack and light, perhaps in the forms of signals, was seen by both Union and Confederate sources. Records indicate the Hunley crew was to signal to shore if they were successful in sinking the Union warship.

Robert Flemming, a sailor on the USS Housatonic, was standing bow lookout watch the night the Hunley attacked. About 45 minutes after the attack, Flemming – who survived and retreated to the Housatonic’s rigging to await rescue – said he spotted a blue light on the water, just ahead of the USS Canandaigua, the first Navy ship to arrive on the scene.

“When the Canandaigua got astern, and laying athwart of the Housatonic, about four ships lengths off, while I was in the fore-rigging, I saw a blue light on the water just ahead of the Canandaigua, and on the starboard quarters of the Housatonic.” – Robert Flemming

Flemming’s report of a blue light could be consistent the testimony of Confederates at Battery Marshall, who said Dixon said he would show “two blue lights” when he wanted a signal fire lit on the beach of Sullivan’s Island.

In addition to Flemming’s testimony, we have two others:

Lieutenant Col. Dantzler at Battery Marshall reported on February 19th 1864, ”The signals agreed upon to be given in case the boat wished a light to be exposed at this post as a guide for its return were observed and answered.”

In 1866, Jacob Cardoza recounted, “The officer (Dixon) in command told Lieutenant-Colonel Dantzler… if he came off safe he would show two blue lights. The lights never appeared.”

Was Flemming the last man to see the Hunley for more than a century? If he was, his account could suggest a tragic end for the Hunley. If the submarine was “just ahead” of the Canandaigua, which was sailing to rescue Union sailors, it could have created a wake that toppled the submarine or hit it directly. Also, because the Hunley had no ports facing aft, the crew might not have even known a ship was bearing down on the submarine.