Clemson University conservators have uncovered new evidence that may help explain why the Hunley submarine vanished off the coast of Charleston, S.C. The new discovery resulted from the long, painstaking process of removing concretion—the rock-hard layer of sand, shell and sea life—that gradually encased the Hunley during the nearly 136 years she rested on the sea floor.

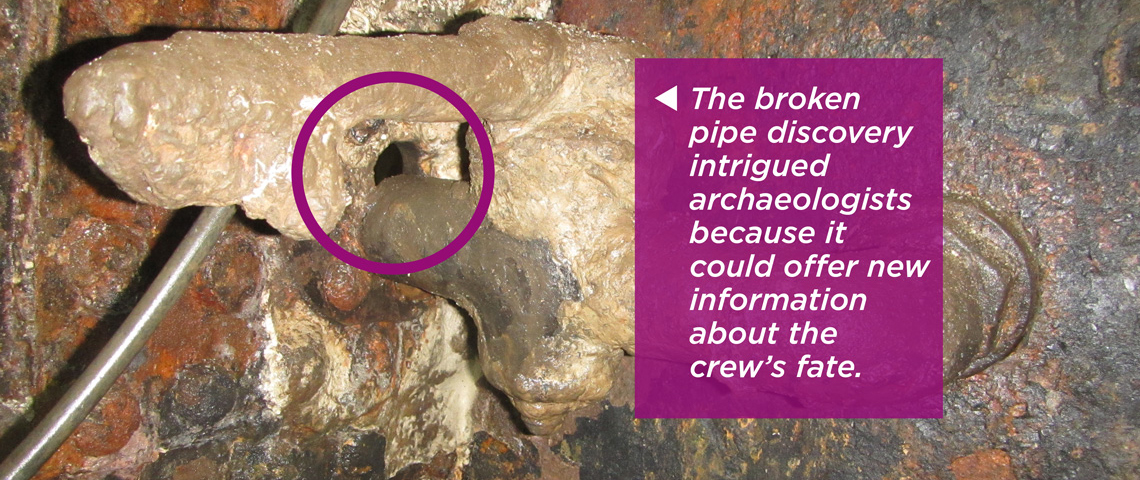

Removing the concretion led to several clues helping scientists piece together the events that led to the loss of the world’s first successful combat submarine. The most interesting discovery was a broken pipe that may have caused water to flow into the submarine the night the crew perished.

NO EASY ANSWERS

The in-take pipe was meant to fill the forward ballast tank with water, but scientists found a roughly 1-inch gap from where the pipe should have been mounted on the side wall of the submarine. If the pipe broke off the night of the Hunley’s historic mission, it may have contributed to the sinking of the submarine and the loss of her crew.

This new evidence is not conclusive. The pipe could have become disconnected slowly over time while the Hunley was lost at sea. “Unfortunately, there are no easy answers when investigating what led to a complex 150-year-old sinking. Still, this is a very significant discovery that will help us tell the full story of the Hunley’s important chapter in naval history,” said Clemson University Archaeologist Michael Scafuri.

DID BROKEN PIPE CAUSE HUNLEY TO SINK?

The Hunley disappeared in 1864 after sinking the USS Housatonic, marking the first time a submarine successfully sank a warship in combat. She would remain lost for over a century until New York Times best-selling author Clive Cussler located her in 1995. The Hunley was raised in 2000 and sent to a laboratory in North Charleston, S.C. to be preserved. Scientists have had a difficult time studying an artifact they could not fully see until the layer of concretion was removed. Now they can finally see the finer features and operations of the innovative submarine that forever changed naval history.

The broken pipe discovery intrigued archaeologists because it could offer new information about whether the crew drowned or died from lack of oxygen. If the pipe did burst the night of the attack, the submarine would certainly have taken on water. But would it have been enough to drag the vessel down to the ocean floor? Researchers at the University of Michigan, who partnered with Clemson University and the Office of Naval Research on the Hunley investigation, say yes.

They calculate it would have taken only 50-75 gallons of water to disable the submarine. Using the size of the hole and dozens of other factors in their modelling, they concluded three minutes of unrestricted flow through the breach would sink the submarine.

Given the size of the hole, however, the water could have been significantly slowed with a cloth or other item to block it. And, the crew did not have the valves set to bilge in order to pump water out of the crew compartment, a move they most certainly would have taken to save their lives.

Another possibility is the pipe could have simply broken over time while the submarine rested on the sea floor for over a century. Archaeologists say the pipe was already under stress given the way it was mounted to the curve of the hull, making it a likely fracture or failure point. More study of this area will help us understand whether it broke off naturally overtime or was sheared off by an impact or explosion backlash during the attack on the Housatonic.

Removing concretion from the inside of the crew compartment produced other interesting discoveries, including the discovery of more human remains. A tooth was found near where it is believed Frank Collins sat. His remains were buried in 2004 alongside his crewmates and others that lost their lives in the testing and development of the Hunley. They also uncovered innovative operational features, including a complex gear system that helped enhance the output of the crew’s hard work when cranking the submarine.

Removing the concretion was physically and mentally exhausting. Conservators stayed curled up in various awkward positions for hours working in the small crew compartment. One mistake, drop of a tool or slip-of-the-hand could cause permanent damage to the fragile artifact.

Johanna Rivera-Diaz, a Clemson University Conservator spearheading the deconcretion project, said, “Removing the concretion was a slow and challenging task for all of us involved, but the ability to get an up-close look at the true surface of the submarine after all this time has made it entirely worth it.”

Now that the Hunley has been mostly cleaned of this material, the vessel will sit in a conservation bath for approximately five years to preserve the metal and make her ready for permanent public display.