Recently Uncovered Records Reveal Crewmember Originally Thought to Have Died on Hunley Survived the Civil War

A truth of studying history is that no matter how much you think you may

know, history can still surprise you. Hunley researchers have experienced this often during their continued exploration into the scattered documents, diaries, military records, and letters that survived the Civil War. Most recently, the team uncovered records that have proven vital in the quest to identify two of the submarine pioneers whose remains were found within the crew compartment. The new information has taught us the name of one crewmember. At the same time, it created another mystery when it was discovered that a man once thought to have lost his life on the submarine survived the War.

A Sacred Cause

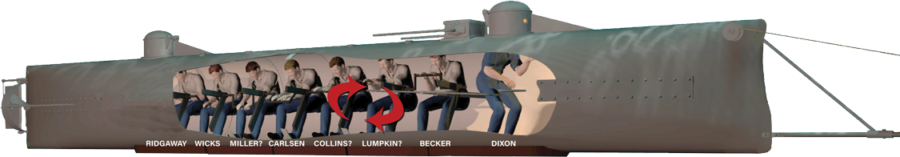

Identifying the dead found on the submarine has long been a solemn – and challenging – cause for the Hunley Project. In 2004 the 8-man crew was buried at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina alongside other men who lost their lives during the testing and development of the Hunley. Leading up to their funeral, facial reconstructions were done based on their skull and preliminary identifications and biographical information were assigned to each crewmember.

The goal was to have the face and personal history of each man who died furthering submarine development remembered at their interment. Most of the identifications have been proven correct, one even resulted in a DNA match with a living descendent. But now new information is impacting two of the preliminary identifications.

Frank Collins Survives the War

A few contemporary letters mention a Collins having been onboard during the submarine’s final, history-making voyage. Collins was a very common last name during the Civil War, which made researchers’ job even more difficult as they tried to locate the man who died on the Hunley.

Still, they got lucky and found a Frank Collins born in Fredericksburg, Virginia that appeared to fit the bill. He shared the same age range as the man stationed at the 3rd crank position and was born in the same region based on forensic analysis.

Everything seemed to fall into place…that is until records were recently found that showed the Frank Collins of Fredericksburg, Virginia had lived in a veterans’ home in Washington D.C. long after the war ended. This required a new avenue of research that has led to the identification of a man previously only known as “C. Lumpkin.”

Identification of Lumpkin

Like Collins, there were only a few 19th century records that show a Lumpkin associated with the Hunley. The older man at the 2nd crank station was originally thought to be that man, sitting next to Frank Collins.

Several years ago, a follower of the Hunley story contacted the Project inquiring whether Cincinnatus Lumpkin could possibly be the same man. Several Confederate Army and Navy records were located for a Cincinnatus Lumpkin, showing army and later naval service as a quarter gunner.

At the time, he was ruled out because the age range and birthplace did not match the remains originally thought to belong to Lumpkin. Now, with the new information discovered on Frank Collins showing he was not the same one found on the submarine, could the man formerly thought to be Collins actually be Cincinnatus Lumpkin?

The man stationed at that crank position was somewhere between 23 and 26 years old. With a birth date around 1841, Cincinnatus Lumpkin was

the right age and the name certainly matched. This was more than enough to have researchers explore the lead further.

Tracking Down C. Lumpkin

Almost immediately, more and more pieces started to fit together. Cincinnatus Lumpkin was born in Drysdale Parish, King and Queen County, Virginia. His parents owned a profitable farm. When the Civil War broke out, Lumpkin and his older brother Bolivar enlisted and were assigned into the King and Queen Artillery, Virginia Volunteers. Lumpkin was transferred to the C.S. Navy in September 1861 and was assigned to the Naval Battery at Gloucester Point.

A lack of historical records hides Lumpkin’s specific whereabouts until July 1863 (his older brother Bolivar was wounded in battle and died in 1862). After abandoning Gloucester Point, both the Confederate Army and Navy fell back to defensive points around Richmond. It is in this timeframe that it appears Lumpkin made his way to Charleston to meet his fate onboard the Hunley.

Follow the Money:

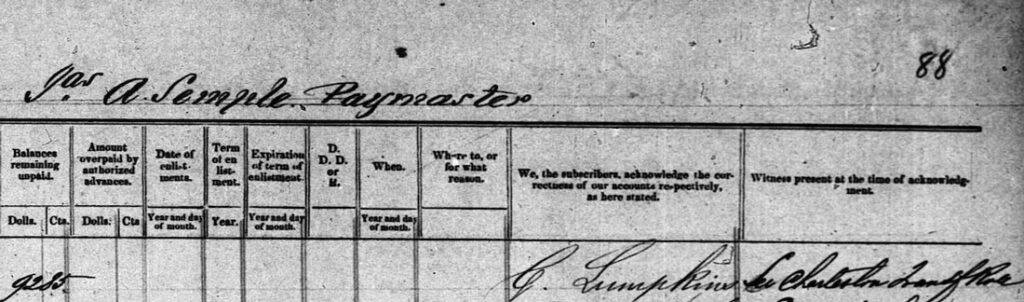

Payroll Records Hold Vital Identification Clue

In 2021, Richmond Station payroll records were found for Dewry’s Bluff Naval Unit (where Lumpkin had been assigned). The document shows quarter gunner “Cinc. Lumpkin” receiving pay for the 1863 quarter ending September 30 and also ties Lumpkin to Charleston, South Carolina. The amount of Lumpkin’s pay carried forward, and held by the government, was $92.85. The witness signature block is not signed, but states “Charleston Transf Roll,” indicating he was sent to Charleston.

Next, Lumpkin appeared in a Charleston payroll record for the Confederate receiving ship Indian Chief — a vessel that three other crewmembers served on before volunteering on the Hunley.

The paymaster list of 31 October 1863 recorded a C. Lumpkin, quarter gunner, serving onboard in Charleston for the period 1–31 October. The pay sheet shows he was owed $92.85 from pay for the prior pay period, exactly matching the amount Lumpkin was owed when he left Virginia.

This document provides compelling evidence tying Hunley’s Lumpkin to young Cincinnatus from Virginia. Not only did they have the same name and were both quarter gunners, but the exact amount of pay was carried forward from one payroll to the next.

LESSONS FROM LUMPKIN’S REMAINS & PERSONAL ARTIFACTS

At 6 feet tall, Lumpkin was the tallest man found onboard, dispelling the notion that Hunley crew members were small so they could fit into such a tiny vessel.

Several insights gleaned from his remains support the identification. His birth year of 1841 matches the age estimate. His isotopic signatures (based on diet and other area-specific environmental factors held in bones) are consistent with a birthplace in Virginia.

Little can be learned about Lumpkin from his clothing or personal effects. He wore no military buttons, despite having served in both the Confederate Army and Navy. Among the artifacts found with his remains were a thimble, a canteen, and standard brogan shoes. Perhaps the most unique find was a small cameo button. This was the only decorative button onboard among all the utilitarian items found in the crew compartment. It may have been a stylistic choice by the wearer, or possibly a keepsake from a loved one.

WILL THE HUNLEY CREW BE ACCURATELY IDENTIFIED?

It’s clear that the Hunley is nowhere near finished giving up her secrets. Will we be able to identify the eight sailors from the United States and Europe whom the tidal forces of war brought together on a fateful night in 1864 to make world history? Modern advancements may help unravel many of these century-old mysteries.

The ongoing digitalization of historic records has made a staggering impact on the amount of Civil War information available. The popularity of online databases such as Family Tree DNA and Ancestry.com has created a vast new trove of publicly available genetic data for researchers to use. With the world having changed so much – making new information much more accessible – since the remains were first discovered in 2000, researchers are hopeful to one day be able to fully tell the full story of the submarine and the men who powered her.

USING SCIENCE & HISTORY TO IDENTIFY THE CREW

The ongoing effort to identify the crew has been multi-disciplinary. Through a combination of historical research, archaeological and genealogical information, and osteological analysis of the skeletal remains, it becomes a process of elimination and data alignment. For example, the remains can tell us the age range and region of birth. If the historical documents and military records on age and birthplace match the forensic data, we can start to narrow in on the crewmember’s identity.

Even with this complex process, a truly positive identification can only come from a DNA match with a descendent. One such match has taken place with a crew member and researchers are confident in the likelihood of correct identifications for a majority of the crew. Hunley Captain Dixon made identification easy given his location in the Captain’s seat and because he was found with many artifacts bearing his name and or initials.

3D Mapping of Hunley Crew Compartment