HIGHLIGHTS:

- The Hunley’s air circulation system didn’t work or was disconnected the night she and her eightman crew vanished in 1864.

- The Hunley could hold enough oxygen for the crew to survive for about two hours before having to replenish fresh air.

- Important clue for researchers to consider when trying to solve this century-old maritime mystery.

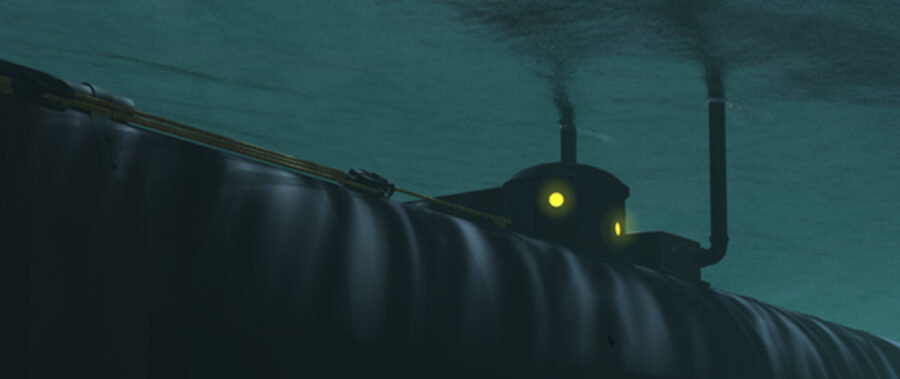

Clemson researchers working to understand why the world’s first successful combat submarine vanished have uncovered an important new clue in their investigation. The Hunley’s air circulation system was not in use when the experimental underwater vessel and her eight-man crew disappeared over a century ago.

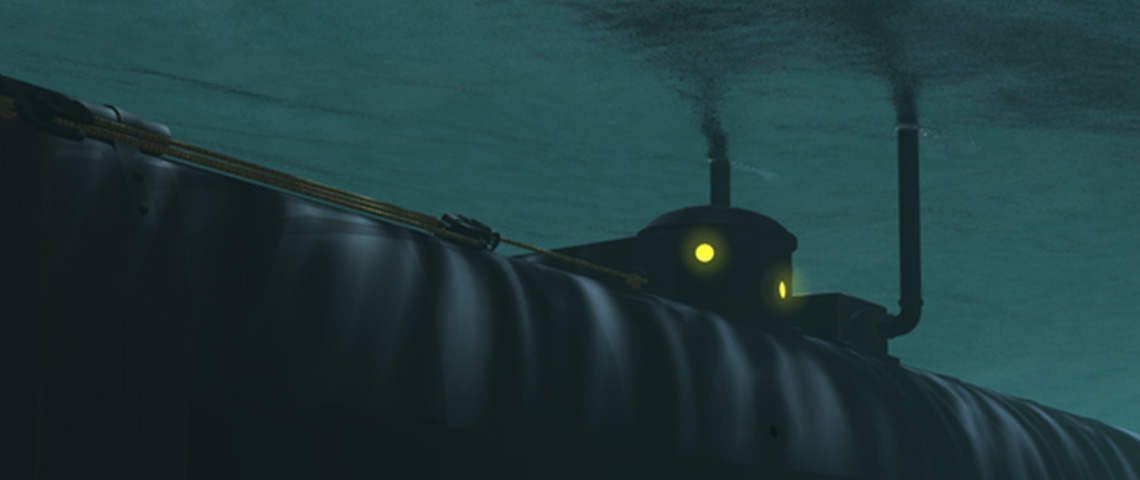

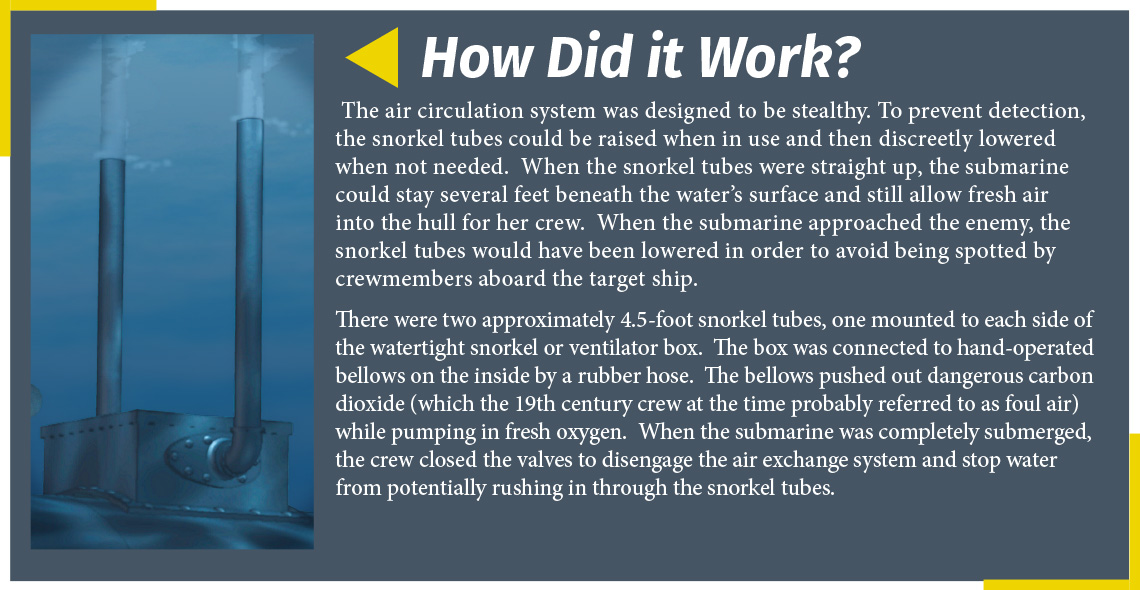

The Hunley was no different than modern day submarines. Their success was based on their ability to remain undetected. The Hunley could hold enough oxygen for the crew to survive for roughly two hours. There were only two ways to replenish oxygen. One was to use the air circulation system, which was designed to be stealth and allow them to discreetly get fresh air. The only other alternative was to come to the surface and open the hatches, a potentially dangerous move if enemy ships were nearby.

The USS Housatonic was one of many Union ships blockading Charleston Harbor during the Civil War. When she was sunk by a surprise attack from the Hunley, it created confusion on the sea that night in 1864. Almost immediately, other ships came to the aid of the Housatonic to rescue the survivors. It is possible the Hunley was surrounded. This would have left the submarine with very few options to escape, unless they could remain unnoticed.

The crew may have attempted to stay beneath the water’s surface until it was safe to try to make their way back home. If they miscalculated the timing or thought it was too dangerous to come back up to open the hatches for air, they may have slowly run out of oxygen to breathe.

“The air circulation system is certainly one of many important clues to consider when trying to piece together the events of that night. Still, this finding alone does not mean the Hunley crew perished from lack of oxygen,” said Clemson Archaeologist Michael Scafuri.

Scientists say it is possible the builders were unable to perfect the design or, when the system was not in use, they dismantled it to make more room in the cramped crew compartment. Or perhaps they simply didn’t think they needed it that night.

We may never know why it was disabled. It appears the rubber hose connecting the snorkel tubes to the hand-pumped bellows was intentionally disconnected and tucked underneath the crew bench. The snorkel tubes were also set to the lowered position and not engaged when the submarine was lost.

Using Science to Save the Air Circulation System

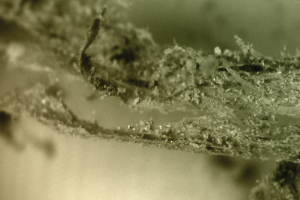

The air circulation system was highly corroded after years in saltwater, making its conservation a very delicate and complex procedure. The system has brass, wood, leather, rubber and iron components, each requiring a separate conservation treatment. The preservation work on the collection was recently completed and showcases the capabilities of the highly skilled Clemson conservation team. The artifacts will now be available for future generations to learn about the origins of submarine warfare.

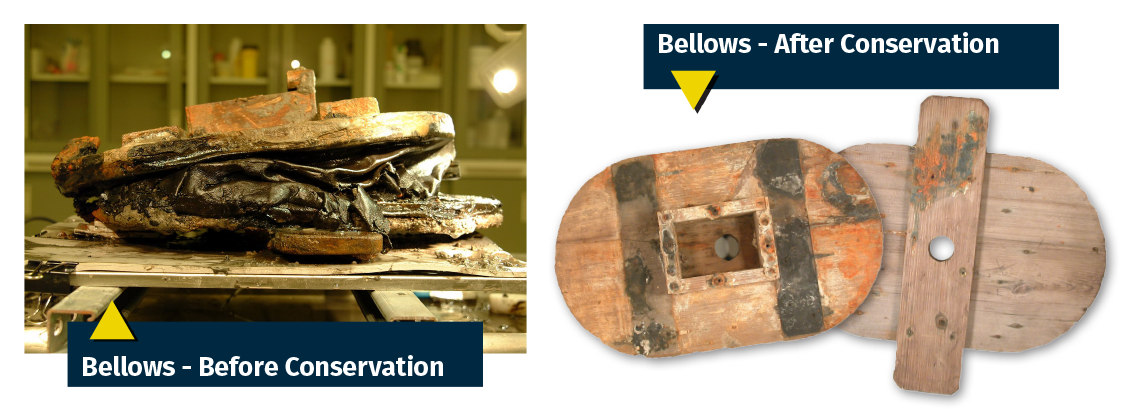

The Leather & Wood Bellows

The wood components of the bellows were separated from the leather for conservation treatment. The bellows were cleaned with chemicals to reduce iron contamination. They were then treated with polyethylene glycol and vacuum freeze-dried. The team was able to retain the shape of the leather of the bellows, quite a feat considering they were deteriorating in saltwater for over a century.

![]()

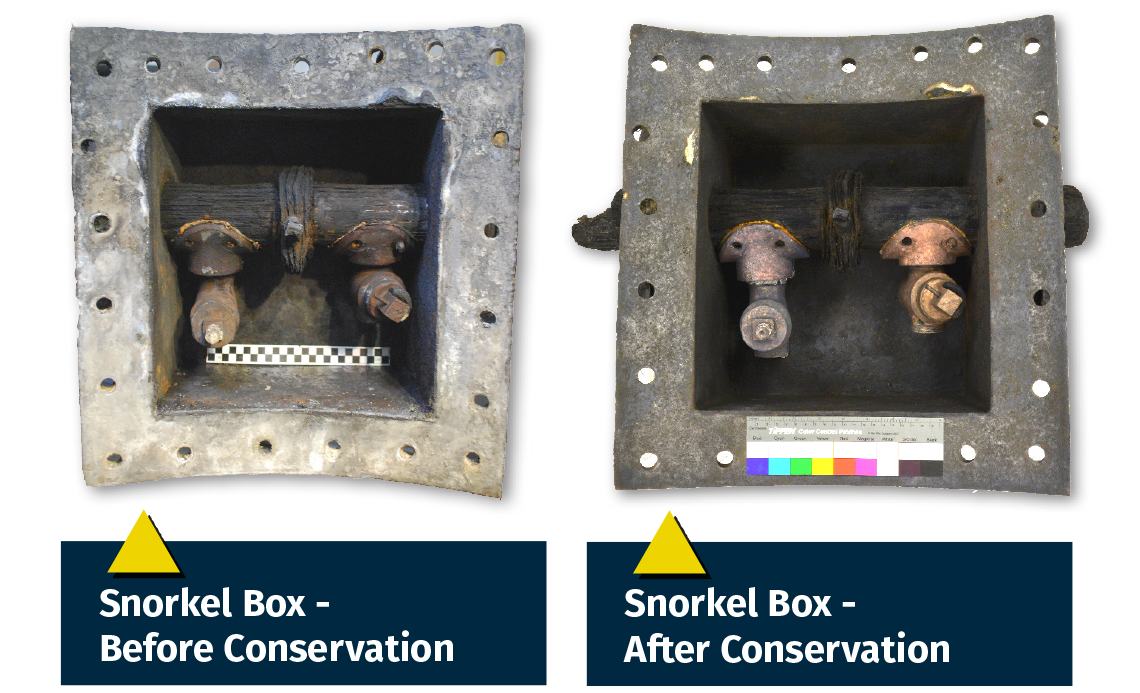

SNORKEL BOX

The snorkel box and tubes have just finished a multi-year conservation treatment. First, they were soaked in solution of sodium hydroxide to pull out the salts that had infiltrated the iron after over a century at sea. An impressed current was also applied to the snorkel box to prevent further iron corrosion caused by the presence of the brass components.

After soaking, the snorkel box and tubes were dried and cleaned to remove layers of corrosion. Then, protective coatings and rust inhibitors were applied to the artifacts. The artifacts are now well-preserved for future generations, a testament to the capabilities of the highly skilled and talented Clemson conservation team.

![]()

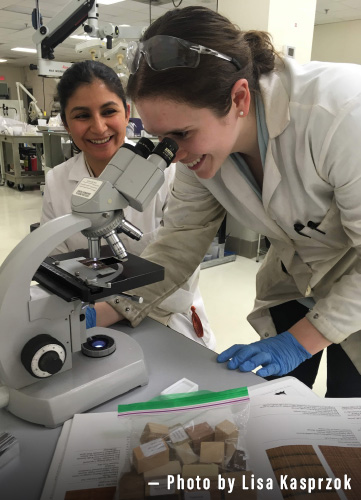

DELICATE PROCEDURE

Saving this collection of artifacts was a complicated and delicate procedure. The system has brass, wood, leather, rubber and iron components, each requiring a separate conservation treatment. Clemson Conservators Johanna Rivera-Diaz and Gyllian Catriona Porteous explain how they saved these fascinating maritime artifacts.