James A. Wicks experienced his share of danger throughout his life, and even survived a famous maritime battle during the Civil War, while serving as a Union sailor.

Thanks to information available from his family as well as Union records, we know a good deal about Wicks. For example, we know he was born in North Carolina around 1819, one of only three members of the Hunley crew born in the South.

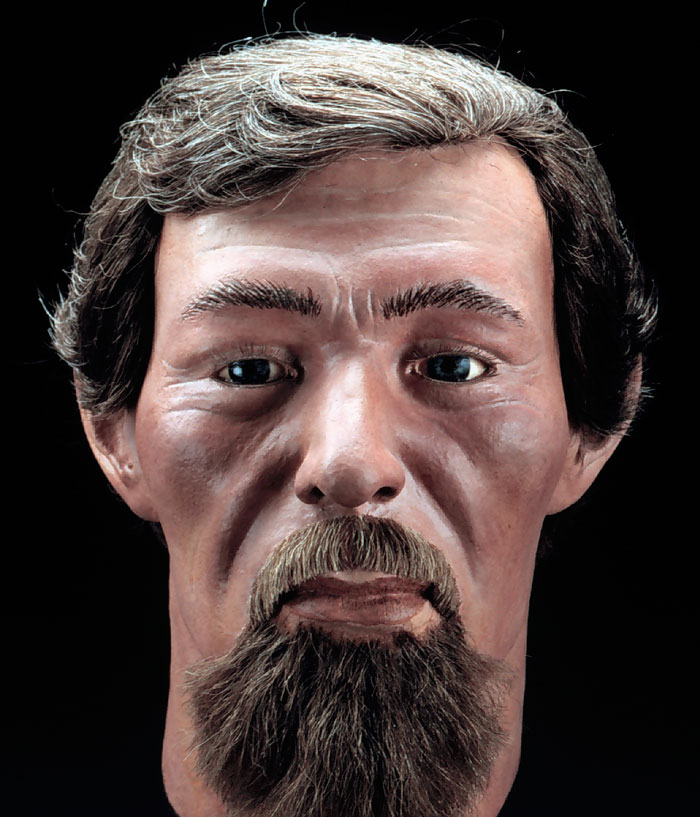

According to forensic analysis, Wicks grew up to be a robust young man, standing nearly 5 feet 10 inches tall and was a heavy tobacco user. In 1850, in his early 30’s, Wicks joined the United States Navy and for over a decade served first as a Seaman and later as a Quartermaster. But his life was soon to become complicated.

The same year he joined the Navy, in 1850, while stationed in Brooklyn, N.Y., the young sailor married and, over the ensuing years, became the father of four girls. When the Civil War began, his wife and children were living in Fernandina, Florida. Meanwhile, Wicks was called into service in a war against his native region, where his family lived. We can only assume that this created for Wicks a sense of conflicted loyalties.

As a sailor in the United States Navy, Wicks served first on the USS Braziliera and later the USS Congress. His job kept him at sea much of the time.

When the War began, Wicks may have wanted to be closer to his family and he may have wanted to fight on the side of his homeland. Circumstances, however, made it literally difficult for him to jump ship. In March 1862, he would have his chance.

While serving onboard the USS Congress, Wicks witnessed the famous onslaught of the ironclad CSS Virginia (formerly known as the Merimac) at the Battle of Hampton Rhodes in the waters off of New Port News, Virginia. The Virginia sank the USS Cumberland and crippled the Congress. The very next day the Confederate ironclad engaged in her famous battle with the USS Monitor.

When Wick’s ship was destroyed off the coast of a Southern state, he was given the opportunity to enter Virginia and cross to the other side of the battle lines. That he did, on April 7, 1862. In Richmond, Virginia, Wicks enlisted with the Confederate Navy and was classified as a Seaman.

Now fighting on behalf of the Confederacy, Wick’s first assignment was to the CSS Indian Chief. With good service, over time, he was promoted to Boatswain’s Mate, an assistant to the officer who controls the work of other seamen.

When Dixon, the Hunley’s commander, was gathering his volunteer crew for the dangerous journey of the experimental submarine, Wicks was one of five crewmembers selected from the Indian Chief.

However, even before the Hunley’s mission was launched, Wicks was called to serve in another daring assignment. In early 1864, he took a brief leave from his Hunley duties to participate in a raid outside of New Bern, North Carolina. The night raid, conducted by a small group of Confederates, led to the destruction of the Union ship Underwriter. After completing that mission, on February 5, 1864, Wicks was sent back to Charleston and must have arrived only days before the Hunley’s final voyage.

His assignment was to man the Hunley’s sixth crank position. Wicks’ responsibilities included operating the crank and, in case of emergency, his job was to release the aft keel block.

Maria Jacobsen, Senior Archaeologist on the Hunley project said, “During excavation, we found a keel release mechanism below the station manned by Wicks.” Also, if something were to happen to Ridgaway, the second-in-command, Wicks would have taken over his duties. Wicks’ remains were found associated with seven US Navy buttons, which is consistent with his military service.

Linda Abrams, a forensic genealogist researching the Hunley crew, said, “Wicks surviving relatives and his service in the US Navy have enabled me to learn much about the appearance of this man. According to records, he had light brown hair, blue eyes, and a florid complexion.”

Two of Wicks’ daughters had children. Descendants of his oldest daughter were in Charleston, South Carolina on April 17th for the burial of their ancestor, James A. Wicks, an extraordinarily brave man and a true pioneer in maritime history.