(Charleston, SC) — In 1864, the H. L. Hunley shocked the world when she became the first submarine to sink a ship by an underwater attack. Now scientists are learning the Hunley not only changed naval warfare by the way she traveled, but possibly also by the use of electrically detonated explosive technology.

The Hunley may have employed one of the earliest, if not the first, electrically detonated explosives being launched by a ship. Electric detonation of a spar torpedo was not perfected by the British until the 1870’s.

Senator Glenn McConnell, Chairman of the Hunley Commission, said, “The Hunley continues to prove that she was a high-tech machine that was generations ahead of her time.”

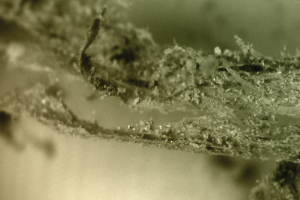

Over the course of the submarine’s excavation, scientists have found a number of tantalizing clues that point to a battery being aboard the Hunley. A metal plate was recovered near Hunley commander Lt. George Dixon’s station. The plate is approximately 4 inches wide, 16 inches long, 1/8 of an inch thick, and has a series of holes running along its perimeter, meaning it was most likely mounted to something or one component of a much larger device.

Preliminary surface analysis of the plate shows it has zinc and copper elements, the two main ingredients needed for a 19th century battery.

For a battery to be used to send an electric charge to detonate the torpedo, wire connecting the energy source to the torpedo would have been needed, and there is no shortage of wire on the sub. Near the plate, scientists found a copper wire with a looped end and there is a large spool of deteriorated wire hanging from the upper bulkhead in the forward ballast tank. If the plate proves to be part of a battery, the wire remnants recovered may have been part of the overall construction of an electric detonation system for the torpedo.

“All this wire was found within reach of Lt. Dixon, the man responsible for detonating the torpedo,” said James Hunter, archaeologist with the Hunley project.

The Hunley used an innovative lanyard system to detonate the torpedo. The idea was to ram the spar torpedo into a target and then back away, causing the torpedo to slip off the spar. A rope from the torpedo to the submarine would spool out. Once the submarine was at a safe distance, the line would tighten and detonate the warhead.

There was no guarantee the torpedo would detonate. Also, a potential danger with the rope spool may have caused Hunley’s designers to turn to an electrically detonated lanyard system. The rope attached to the spar could get caught on ocean debris, possibly triggering a fatal explosion for the Hunley and her crew.

“We had two pumps and deadlights re-enforcing the glass ports along the top of the submarine. If the torpedo could also have been electrically detonated, this would be right in-line with the Hunley having fail-safe measures in place for all her critical functions. This could be a cutting edge upgrade to an already state of the art firing system,” McConnell said.

Electrically detonating the torpedo would have given the Hunley crew a key advantage by being able to control when the explosion occurred and ensure they were a safe distance from their target.

History shows the Hunley’s delivery of the torpedo evolved as testing was done. Originally, a contact mine was towed behind the submarine, but eventually the submarine was fitted with a bow-mounted spar torpedo.

If the plate and wire turn out to be part of an electrically detonated torpedo design, it would not be the first time Hunley designers attempted to use high tech technology to maximize the sub’s effectiveness as an underwater weapon. One of the Hunley’s predecessors, the American Diver, had originally been engineered to use an electromagnetic engine to propel the vessel. The Hunley’s builders returned to the hand-cranked design when they were unable to generate enough horsepower to achieve speed levels that were needed for a stealth attack.

Further research on the plate is needed and the construction of the sub to determine whether the Hunley indeed used an electric torpedo.

Concretion on the hull is still inches thick near Dixon’s station, and scientists are hopeful more plates and wire will be discovered. “The discovery of this plate was an intriguing find,” said Paul Mardikian, Senior Conservator to the Hunley project. “We cannot rule out the possibility of having some sort of electrical device on the submarine. Next week, Clemson University will be analyzing the plate and we will have a much better understanding of what we’re dealing with here.”

Additionally, concretion still masks many features of the Hunley’s bow that may help reveal how the torpedo was rigged to the vessel. Once that concretion is removed, scientists expect more details will come to light about how the Hunley was designed and was able to achieve her history-making feat.

On the evening of February 17, 1864, the H. L. Hunley became the world’s first successful combat submarine by sinking the USS Housatonic. After signaling to shore the mission had been accomplished, the submarine and her crew of eight vanished.

Lost at sea for over a century, the Hunley was located in 1995 by Clive Cussler’s National Underwater Agency (NUMA). The hand-cranked vessel was raised in 2000 and delivered to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where an international team of scientists are at work conserving the vessel and piecing together clues to solve the mystery of her disappearance.

The material included in this press release is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service and the Legacy Resource Management Program.