(April 14, 2004 – CHARLESTON, SC) – The man we know only as Miller may be the most elusive member of the crew of the

H. L. Hunley, the world’s first successful combat submarine. About him we know only a few sketchy details.

Miller stood 5 feet 8 inches tall, above average for a man of the Nineteenth Century. Yet, he was one the smaller members of the crew. “Most people think that the Hunley crewmembers were men of a small stature so that they could enter and work inside the submarine. We have been surprised to find most of the crewmembers were relatively tall men for their era,” said Maria Jacobsen, Senior Archeologist on the Hunley project.

Forensic analysis indicates Miller was from Europe and had been in America for a relatively short period of time before he volunteered as a crewman for the Hunley. One of the two oldest crewmembers, Miller’s age at the time of his death has been estimated at somewhere between 40 and 45 years.

Evidence suggests he lived a life marked by injury and harsh physical activity. He suffered fractures on his rib, leg, and skull. Doug Owsley, forensic expert with The Smithsonian Institution, said, “This crewmember was a heavy smoker and suffered from the beginning stages of arthritis.” Though he could not smoke on the submarine, Miller still carried a wooden pipe onboard the Hunley, which was found during the excavation of the hull.

There is no shortage of men with the surname Miller who served in the Confederacy, which makes if difficult for experts to trace which Miller it was who perished in the Hunley. Documentation suggests Dixon found two volunteers from the German Artillery, one of which was J. F. Carlsen. There was a Samuel Miller who served with Carlsen on the Jeff Davis. Samuel Miller was captured by Union forces and released in 1862.

Linda Abrams, forensic genealogist researching the Hunley crew, is still attempting to find out more about the mystery man. “Right now, I am trying to determine if the Miller that served on the Jeff Davis returned to Charleston,” she said. The remains of the crewmember we know as Miller were found associated with two Confederate infantry buttons, which would be consistent with service in the German Artillery.

If we ever determine that the Samuel Miller who served with Carlsen on the Jeff Davis did indeed return to Charleston before the Hunley launched its fateful mission, he will be a likely candidate as one of the eight marine pioneers who took the Hunley on its historic journey.

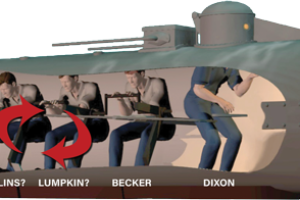

Miller was most likely sitting at the fifth crank position. His only duty was to operate the crank. Based on his position, he may have been one of the last members to join the team.

“All we really have on Miller is a last name. He is a real mystery man,” Jacobsen said.

Miller’s life ended creating both a maritime first and another mystery. Why did he and his seven crewmates vanish after navigating the world’s first successful combat submarine?

On the evening of February 17, 1864, the H. L. Hunley became the world’s first successful combat submarine by sinking the USS Housatonic. After signaling to shore that the mission had been accomplished, the submarine and her crew of eight vanished.

Lost at sea for over a century, the Hunley was located in 1995 by Clive Cussler’s National Underwater Agency (NUMA). The hand-cranked vessel was raised in 2000 and delivered to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where an international team of scientists are at work conserving the vessel and piecing together clues to solve the mystery of her disappearance.

The Hunley project scientific staff worked with forensic expert Doug Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution and forensic genealogist Linda Abrams to identify the remains of the Hunley crewmembers. They did this by combining the archaeological and genealogical information with the osteological analysis of the skeletal remains. For example, the remains can tell us the age range and region of origin for each crewmember. If the genealogical information on age and birthplace match the forensic data, they can estimate the crewmember�s identity through the process of elimination. However, a completely positive identification of each crewmember can only come from a DNA match with a descendant.