(April 12, 2004 – CHARLESTON, SC) – Arnold Becker was not a native of the South. He was not even born in America. In fact, when he became a crewmember of the world’s first successful combat submarine, he had not been living in the United States for very long.

Dr. Doug Owsley, forensic expert with the Smithsonian Institution, says his remains show indications of strenuous physical activity. “His teeth have linear growth disturbance lines that were most likely caused by childhood illnesses or bouts of malnutrition,” Owsley said.

No matter how difficult his life may have been in his homeland or the reasons for his departure, his new start in the United States would quickly lead him to a new hardship, the frontlines of The Civil War.

When the War began, Becker may have been working on a riverboat on the Mississippi purchased by the Confederate government. The riverboat was re-fitted for battle and re-named the CSS General Polk. That seems to be a likely port of entry for Becker in the conflict.

Whatever the specific circumstances, on October 19, 1861, Becker joined the Confederate States Navy and was assigned to work on the reconfigured riverboat to which he may have already been accustomed. On June 26, 1862, the General Polk was destroyed by a fire. The fire was started by her own crew in order to avoid capture.

A year later, by October 1862, Becker was working onboard the CSS Chicora , a gunboat engaged in launching attacks against Union ships blockading Charleston harbor. During his work on the Chicora, Becker was promoted to the rank of Captain’s Cook, meaning he served as an assistant to the Captain. His name continued to appear on pay rosters of the Chicora until September 1863.

The Confederate States Navy later assigned Becker to the CSS Indian Chief stationed outside Charleston Harbor. While onboard the Indian Chief, Becker would find his place in history. Lt. George Dixon recruited him as one of the volunteers to man an innovative secret weapon called the Hunley, which was the last hope the Confederacy had to break the Union blockade around Charleston.

Standing 5 feet 5 inches and approximately 20 years old, Becker was perhaps the smallest and youngest crewmember of the Hunley. But his age and stature were no indications of his responsibility on the submarine. Becker was seated directly behind Dixon and though he was the 3rd in command of the vessel, the complexities of his duties on the submarine would have been second only to Dixon, the submarine’s commander.

Maria Jacobsen, Senior Archaeologist on the Hunley project, said, “Dixon trusted him, otherwise he would not have assigned Becker to such a critical position on the Hunley. Should something happen to Dixon, Becker was the person most likely to take his place, so he had to be familiar with the general operation and navigation of the submarine.”

Becker operated the bellows and snorkel tubes, the Hunley’s air circulation system that enabled the crew to breathe. He managed the forward pump, and when needed also manually worked the first crank handle. Checking the valve positions and emptying the forward ballast tank when the sub needed more positive buoyancy were also among Becker’s list of duties.

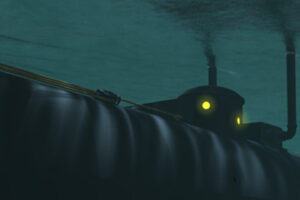

On the evening of February 17, 1864, the H. L. Hunley became the world’s first successful combat submarine by sinking the USS Housatonic. After signaling to shore that the mission had been accomplished, the submarine and her crew of eight vanished.

Lost at sea for over a century, the Hunley was located in 1995 by Clive Cussler’s National Underwater Agency (NUMA). The hand-cranked vessel was raised in 2000 and delivered to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where an international team of scientists are at work conserving the vessel and piecing together clues to solve the mystery of her disappearance.

The Hunley project scientific staff worked with forensic expert Doug Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution and forensic genealogist Linda Abrams to identify the remains of the Hunley crewmembers. They did this by combining the archaeological and genealogical information with the osteological analysis of the skeletal remains. For example, the remains can tell us the age range and region of origin for each crewmember. If the genealogical information on age and birthplace match the forensic data, they can estimate the crewmember’s identity through the process of elimination. However, a completely positive identification of each crewmember can only come from a DNA match with a descendant.