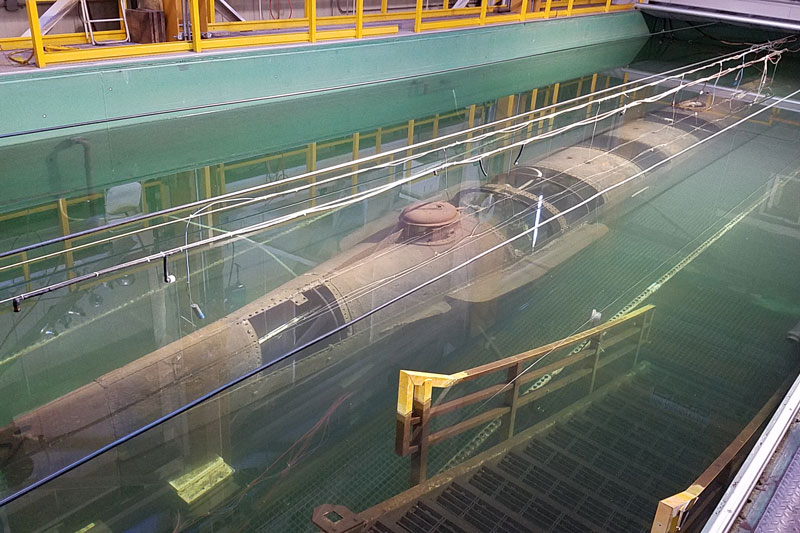

While the Hunley rested on the floor of the ocean for over a century, salt water slowly penetrated her iron skin. The salts weakened the structure and rendered the once strong iron submarine vulnerable to air exposure on land. Unprotected in open air, her hull would rapidly rust and collapse.

Finding a way to reverse the corrosion damage has been a major challenge for conservators. The Hunley is a unique, complex artifact, therefore there was no “textbook” approach to follow for the submarine’s conservation. Additionally, the excavation of the crew compartment produced a large array of fascinating artifacts from the 19th century, some made of cloth, glass, silver, and leather. Each of these elements required different conservation techniques and specific, specialized treatment.

Working with Clemson University, the conservation team has managed to overcome these many challenges. It has been a time-consuming process, but worth the wait as the team is saving our nation’s rich maritime history.

Today, hundreds of personal artifacts from the crew have already been conserved and a plan is well-underway to save the submarine itself. To reach this point was a decade-long journey that began on August 8th, 2000.