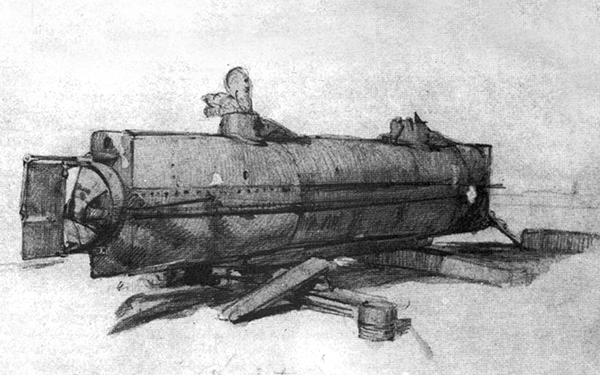

While the H. L. Hunley began her preliminary testing, the news of the defeat at Gettysburg and loss of Vicksburg had reached Mobile. Times were increasingly desperate for the Confederacy. The Hunley was initially designed to dive completely below her target while towing behind a floating torpedo on a 200-foot tether. Once the submarine dove and passed under the keel of her target, the torpedo would impact its hull on the other side, in theory causing a devastating explosion that would sink the ship. To safely dive under a Union vessel, the Captain would need to carefully maneuver the five-foot tall submarine between the ocean bottom and the keel of the target ship.

Satisfied with their submarine’s performance, in July 1863, a demonstration of the Hunley’s attack capabilities took place for Confederate officials.

An old coal-hauling barge was anchored in the middle of the Mobile River. The Hunley approached her mark and then dove beneath the target vessel. When the torpedo hit the barge, it blew up and sank within minutes. The Hunley resurfaced shortly after. After two years of attempts at the submarine concept, it had finally happened. The Hunley had successfully attacked her target.

On site to witness the display were several high ranking officials including Admiral Franklin Buchanan, Mobile’s Naval Commandant. He immediately wrote a report to General P. G. T. Beauregard, officer in command of Confederate forces in the key port city of Charleston, South Carolina. In his account Buchanan said, “I am fully satisfied [the Hunley] can be used successfully in blowing up one or more of the enemy’s Iron Clads in your harbor.” General Beauregard agreed, requesting the “much needed” fish boat be sent at once.

The Hunley was loaded onto two flat rail cars and sent to defend Charleston with the hopes she could help cripple the blockade strangling the city.